Showing VS Telling

Good morning! If you have ever worked with me on a story or book, you will know this is my favorite topic! If you have never heard of these terms before, don’t worry, I’ll explain them first. This post will help you understand what showing VS telling is and how to recognize it in your own writing.

Telling: To tell is to simply tell your reader what is happening without an image.

For example: The girl wore an old shirt.

Showing: To show information means you are presenting ideas to your reader in the form of writing an image.

For example: The girl wore a blue shirt that was tattered at the sleeves and had a small stain.

Instead of telling your reader it is old, show us the stains and tatters instead.

What Does Showing VS Telling Mean?

These terms specifically refer to how you present information to your reader. To show something means you give your reader an image instead of just telling them exactly what is happening. Images in a story are important because this is what your reader will imagine as they read. A good image can be impactful, clarifying, and exciting. If you simply recite actions, feelings, and instances to your reader when you are only “telling” a story, it can get boring fast. More importantly, a reader doesn’t feel immersed into a story where all the information is only told to them, instead of shown.

Talking about showing VS telling can feel intangible pretty fast if you are unfamiliar with the terms. Let’s look at them one at a time before comparing them and seeing how you can spot these ideas in your own story.

Let’s Talk About “Telling”

To tell something means you are literally telling your reader what is happening.

This is the spelling out of actions, thoughts, and feelings which can make your writing sound a little mechanical and wordy. It’s important to create clear and concise phrases, but “telling” can lead to over explaining an image, idea, or action.

Here is an example:

Susan walked to the store and saw a dog down the street. It was a cute dog and made her feel good.

The phrases I have highlighted are what make this a telling statement. The writer is saying there is a dog, it is cute, and it makes the character feel good. While this is all good information, it is telling us straight instead of letting the reader know what this looks like on their own. For example, two different readers can get two different images here. Is a cute dog fluffy? Is it tiny or big? We don’t know because the adjective “cute” does not give us a specific image.

Same for “made her feel good.” We know how she is feeling, but we can’t take part in this. We are told but are not immersed in the moment. (For example, saying a character is “sad” is not as strong as the image of tears rushing down their face.)

Also, because this story is in Susan’s point of view, we don’t need “saw” because everything mentioned in this sentence, we know she is already seeing. I would delete the word “saw” completely because it overexplains this already assumed action.

Showing provides information without telling. It is so the reader feels like they are inside the story themselves, feeling and seeing everything.

Let’s Talk About “Showing”

To show information is to provide an image for your reader to imagine. There are several reasons this is important. The reader feels involved or as if they are standing in the character’s shoes inside the story and are seeing everything for themselves. Another reason, the reader can see an image and make their own assumptions. The old saying that a picture is worth 1,000 words is true here, even though it is made of words in your story… the same idea applies.

Looking at that previous example, here is how you can make it showing instead of telling:

As Susan walked to the store, a fluffy terrier came to greet her. Her cheeks warmed and she broke into a smile.

Here we are shown the dog (a fluffy terrier—specifics are important!) so we can imagine it too and decide for ourselves that it is cute. The last part about her cheeks and smiling show us that Susan is happy. This wouldn’t be the reaction of someone feeling any other way. By showing these details, your readers not only get the same information from this sentence, but we also get some key images. Creating an image, no matter how simple, is very important.

How to Spot Telling in Your Writing

Spotting telling writing in your story is a lot easier than you may think. Stating emotions or actions is usually a strong tell. Looking out for these kinds of words is a great place to start. Here are some examples:

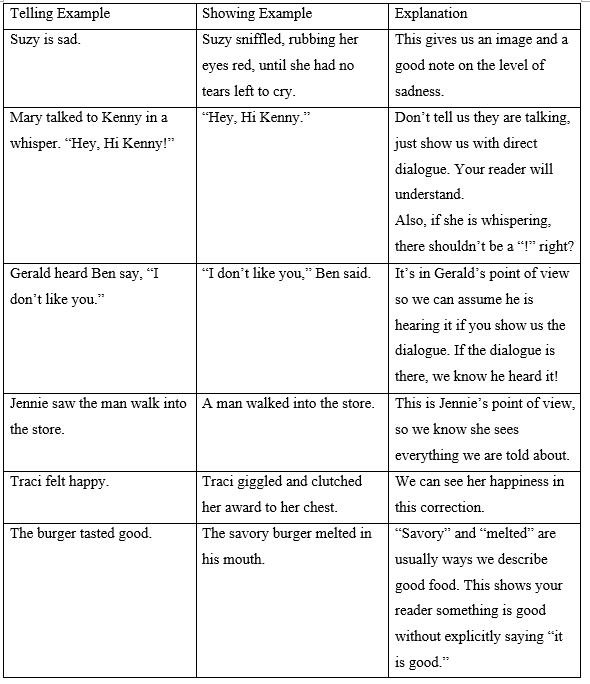

Suzy is sad.

Mary talked to Kenny in a whisper. “Hey, Hi Kenny!”

Gerald heard Ben say, “I don’t like you.”

Jennie saw the man walk into the store.

Traci felt happy.

The burger tasted good.

All these statements do a good job telling us what is happening. We know Suzy is sad, we know Jennie saw a man but, these ideas sound like a list. Telling is a list of actions and emotions in your story that are only told to us. What if your reader could feel these emotions too? How do we do that?

“Suzy is sad.” Gives us the information we need. But what does this look like? This is an ambiguous description because I might imagine she is sniffling and frowning. But you might read this and think she is so sad that she is screaming and crying her eyes out. Thinking those two different things can cause a big problem if you are reading a story and the writer specifically wanted you to think one way or the another. A way to not only clarify this but to also give an accurate image to the reader is to show us instead and leave no room for misinterpretation. “Suzy sniffled, rubbing her eyes red, until she had no tears to cry.” That line gives us a specific image of exactly how Suzy is feeling in this moment.

If Traci feels happy, show us instead. Is she jumping for joy? Is she quiet and smiling? If the story is in Gerald’s point of view, we know he is hearing anything we are reading so the phrase “heard” needs to be removed.

There are some key verbs that are often a part of telling language. You can almost always rewrite these to make a clearer statement.

Key words often used in telling statements:

To hear

To see

To feel

To touch

To listen

To taste

To watch

To talk

If a story is in your character’s point of view, everything they taste, see, touch, say, or hear can safely be assumed as being heard, seen, touched, or felt by your character, unless you tell the readers otherwise. Because this information is known, we don’t need to be told or reminded that they are doing these things on top of what they are receiving in these moments. If there is dialogue, we know the character hears it. If there is an image, we know they see it.

Instead of using these words, show us instead!

Of course, there are many exceptions to these ideas, but this is a good place to start when you are just beginning to use showing VS telling in your writing. If you have a line where you think using one of these verbs are the best choice for the moment, that’s okay! If that wording matches your intentions better, then go for it. What’s important when learning rules like these is to know they don’t fit everything. It’s important to recognize a telling statement and ask yourself, “Does this fit here?” “Can I write this better to show my reader?” If you think the telling statement is the best way to say something, maybe it is. What’s important is that you stopped and questioned it, weighing if there was a better option or not.

The Benefit of Showing and Not Telling

Showing instead of telling can strengthen your writing in many ways. It gives your reader an image, so they feel as if they are right there in your story. Images also give us many more meanings and thoughts, such as showing the intensity of a moment or really making sure your reader is getting the specific idea you want them to.

There is an image I love to use when deciding if your reader is immersed in your text or not. Imagine the reader is watching your story play out on a theater’s movie screen. If a reader is fully immersed into a story of images and feel like they are right there—they are in that front row with those awesome 3D glasses on. They are getting the full experience and are excitedly turning the pages. If your story has a lot of telling, explanatory passages, or is not connecting with the reader, they might feel like they are sitting all the way in the back of the theatre. They feel the distance between themselves and those pages and they have to squint to try to feel attached to the characters.

Showing images, weaving the ideas in your story, and paying attention to the rise of action and tension are all keys to the process. I hope for today, you will feel ready to dive into the ideas of showing VS telling!

Conclusion

I hope you found today’s topic helpful! Showing VS telling is something that can be really hard to find in your own writing. One reason I think it is because you are the writer. When you read your story, your brain knows all the details. You are reading or editing a page, but your brain is filling in all the missing information, images, and more. It’s hard to know if you are really getting all that information down onto the page or not. While looking for an editor, or someone to read your work is the best way to point out these instances, knowing key words and phrases that usually lead to telling statements is a great way to help yourself in this process.

Overall, if you have a manuscript that is all telling—that is not a bad thing! Trust me, I’ve been there. If this is you, look at this as an opportunity. Once you know how to approach this, you will have the tools you need to improve your writing and make it even better. I believe in you and I’m excited for all the writing and editing to come. Happy writing!

Best,

Danni Lynn, Evangeline40003